Minutemen newspaper articles

4 posters

NOW LOCATED AT https://theslaughterhouse.freeforums.net/ :: WE HAVE RELOCATED TO https://theslaughterhouse.freeforums.net/ :: Troy Houghton and the Minutemen

Page 1 of 1

Minutemen newspaper articles

Minutemen newspaper articles

First one I will post is about a threatening letter signed with a crosshair symbol. This, of course, is in reference to the 'Traitors Beware' that I will post below the article.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Dec. 14, 1963 San Bernardino County Sun

Never seen this one before. Montana you say?!?!?!?!

Guess we should look into this William Francis Colley guy. This is the first time I have heard of him, I think.

Never seen this one before. Montana you say?!?!?!?!

Guess we should look into this William Francis Colley guy. This is the first time I have heard of him, I think.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Nov. 11, 1961 Long Beach Independent. There were several front page articles in this newspaper. And, of course, Don Alderman is Troy Houghton.

A truckload of weapons and ammunition seized.

Were these Minutemen weapons?

Minutemen leader arrested:

Alderman (Houghton) sex case:

*There is a photo of Melvin Belli right next to the Alderman article.

A truckload of weapons and ammunition seized.

Were these Minutemen weapons?

Minutemen leader arrested:

Alderman (Houghton) sex case:

*There is a photo of Melvin Belli right next to the Alderman article.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Notice William Francis Colley mentioned again? Looks like he was a photographer that did not get along with Houghton. He has a record dating back to 1939, so was probably pretty old when the Zodiac crimes happened, but I will check and see what I can find out about the guy. A thought I had, since we was arrested with Air Force property in Montana, is what if he was Z ans he tried to frame Houghton by using the Minutemen's logo? I doubt this is the case, but we shall leave no stone unturned. Uh-oh, I said SHALL!!

Last edited by ophion1031 on July 5th 2015, 2:15 am; edited 1 time in total

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Found another newspaper article (Sept. 27, 1963), but it is hard to read so I won't post a picture of it. It says that William Francis Colley and David Kenneth Levesque (sp?), along with four other men, had received approximately $10,000-$25,000 worth of stolen Air Force property from a San Diego Air Force base. Colley and Levesque, who were wanted fugitives, were arrested in a NW Montana cabin they had been hiding out in for a year. Colley was using the alias of Richard Bishop and Levesque was using the alias Lawrence Williams.

In 1961, before heading to Montana, Colley had identified himself as the local San Diego director of the "Loyal Order of Mountain Men," a band of citizens training for mountain survival in case of a nuclear attack.

It's not clear what the feud between Colley and Houghton was, but it seems to imply that they were fighting over leadership of the California Minutemen. I think the article says that police arrested both men as they were about to do battle, and it lead to the police finding a good amount of weapons and ammunition, which is what the articles posted previously pertain to.

Colley and Levesque were sent to Flathead County jail in Montana after they were arrested in the cabin. Because these men, or Colley at least, have links to the Minutemen AND both did time in Montana (Bryan Hartnell claimed that Zodiac told him he had escaped from a Montana prison), I would like to further research the both of them. I have a lot on my plate right now, but I will get around to it. County jail and prison are two completely different things, so one of the things I will try to find out is if these two men actually served prison time as well, and if so, what prison they were in and when they were released.

In 1961, before heading to Montana, Colley had identified himself as the local San Diego director of the "Loyal Order of Mountain Men," a band of citizens training for mountain survival in case of a nuclear attack.

It's not clear what the feud between Colley and Houghton was, but it seems to imply that they were fighting over leadership of the California Minutemen. I think the article says that police arrested both men as they were about to do battle, and it lead to the police finding a good amount of weapons and ammunition, which is what the articles posted previously pertain to.

Colley and Levesque were sent to Flathead County jail in Montana after they were arrested in the cabin. Because these men, or Colley at least, have links to the Minutemen AND both did time in Montana (Bryan Hartnell claimed that Zodiac told him he had escaped from a Montana prison), I would like to further research the both of them. I have a lot on my plate right now, but I will get around to it. County jail and prison are two completely different things, so one of the things I will try to find out is if these two men actually served prison time as well, and if so, what prison they were in and when they were released.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

http://www.columbiatribune.com/news/local/minuteman-outlasted-notoriety-died-with-regrets/article_bc69cd47-d0a5-53b5-a190-bc17f7d6512c.html

In the 1960s if you entered a restroom or a phone booth, there’s a chance you might have noticed a three-inch-square sticker at eye level. A closer look might show the image of a rifle crosshairs superimposed over a menacing text:

“See that old man at the corner where you buy your papers?” the sticker read. “He may have a silencer equipped pistol under his coat. That fountain pen in the pocket of the insurance salesman that calls on you might be a cyanide gas gun. What about your milkman? Arsenic works slow but sure. … Traitors, beware! Even now the crosshairs are on the back of your necks.”

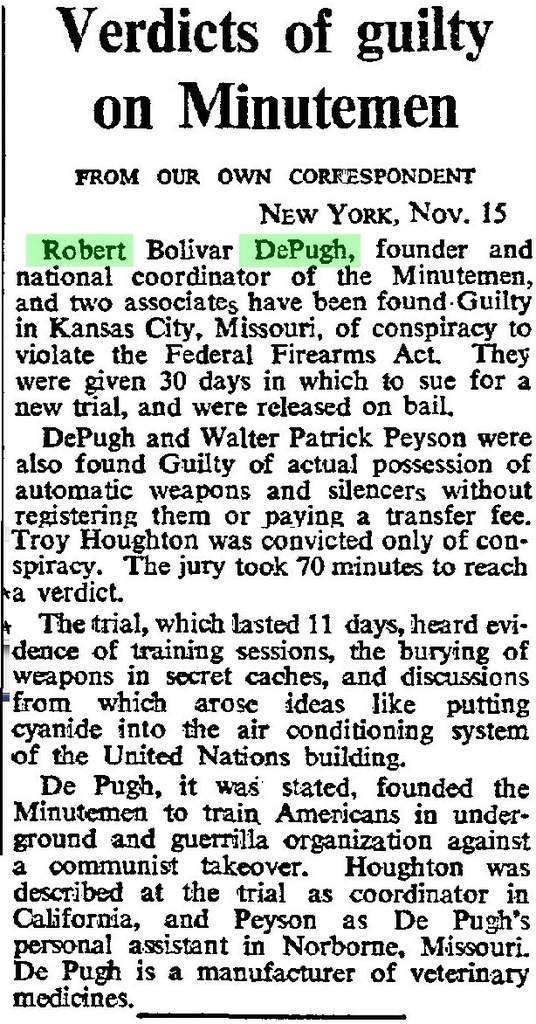

The author of this screed is Robert Bolivar DePugh, and his goal was terror. For more than a decade, DePugh led a shadowy militia group known as the Minutemen. Their stated purpose was to use guerilla warfare to repel the Communist invasion they always believed was at hand. Later, they vowed to root out Communist spies they swore were entrenched in the U.S. government. War, in their minds, was always imminent, and a group of armed patriots was the last best hope for the Republic.

“He saw himself as the Paul Revere of the 20th century, that he was going to save the United States from Communism,” said Eric Beckemeier, who grew up in DePugh’s adopted hometown of Norborne and wrote a book in 2007 chronicling his movement. “It was delusions of grandeur, almost.”

DePugh was named after the revolutionary South American fighter Simon Bolivar and was raised in Independence by a father who was a Jackson County sheriff’s deputy. He bounced around several colleges in the 1940s, including a stint at the University of Missouri. In 1943, he enlisted in the Army but was discharged the next year after a psychological review noted psychoneurosis.

By the late 1950s, though, DePugh was a relative success. He had made a small fortune in veterinary medicine when he founded Biolab Corp. and created a vitamin that promised to lengthen the lifespan of dogs. The tiny town of Norborne, which is about 100 miles northwest of Columbia, actively recruited DePugh to move his company there, believing he would bring jobs.

Instead he brought ignominy.

DePugh used Norborne as a home base from which to recruit dissidents from all over the nation. He printed and mailed out a monthly magazine, “On Target,” and authored several popular books. His themes of self-reliance, ultra-patriotism and paranoid anti-communism struck a chord with people on the fringes.

“Within that little narrow range of people, he was sort of charismatic,” said Harry Jones, a longtime Kansas City Star reporter who covered DePugh and wrote a book about the Minutemen in 1968. “But his ideas were so out of whack with what most people were thinking that the great majority of people laughed him off as a kook.”

But it was impossible to laugh at the cache of arms and explosives DePugh was building up or dismiss his paramilitary training sessions, where men crawled on their bellies and practiced marksmanship and booby-trapping. Loosely affiliated groups began to sprout up in other states under the same Minutemen banner, and DePugh bragged that his network was tens of thousands large. Newspapers repeated his claims.

“Various liberal interest groups and newspapers were giving figures of 50,000 or 100,000 people, and it just wasn’t true,” said Laird Wilcox, an expert on extremists and founder of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements at the University of Kansas. “There were just a few hundred people who were active in that thing. … There wasn’t much of an underground to it at all.”

But DePugh had a knack for the spotlight. He named names of Communists — including Lucille Ball and Humphrey Bogart, among others — and he published a list of 20 congressmen he wanted dead. Attorney General Robert Kennedy ordered his movements closely watched, and FBI agents infiltrated his group.

In 1967, thanks to this federal scrutiny and the vast stores of illegal weapons he stashed around the area, DePugh was convicted of violating the National Firearms Act. Before serving his sentence, he and another Minutemen fled to New Mexico and lived on the lam for two years.

From there on, his life more or less unraveled. In 1969, DePugh was caught in Truth or Consequences, N.M., after a massive manhunt. According to multiple reports, agents found him holding two former Minutemen — a man and a woman — in confinement crates because he believed they were traitors. He also had large stores of weapons. DePugh spent four years in federal prison and wrote a book about the plight of the incarcerated. Many consider it his best and most compassionate work.

During the late ’60s, authorities tried to connect him to various other Minutemen exploits, including a bank robbery in Seattle and a planned cyanide attack on the United Nations, but they were unsuccessful. DePugh credibly said that he had no control over the people who were nominally his followers.

In 1991, police in Iowa arrested him on charges of child pornography after a modeling shoot he took of a teenage girl. DePugh beat those charges as well, but some close to him considered it the last straw and severed their ties to him.

In more recent years, DePugh lived alone in an apartment beneath a storefront church in Richmond, Mo.

Beckemeier, who received a mailing from the prolific polemicist, said DePugh’s political views continued to be bizarre and often contradictory late into his life.

“His writings were anti-Bush, pro-Obama and anti-Semitic, all at the same time,” Beckemeier said. “That’s quite a combination.”

But his life was lonely. His wife had divorced him, and his children mostly had stopped speaking to him. He suffered from ALS disease. Wilcox, who lives in Olathe, Kan., last visited DePugh five years ago and said the man had deep regrets about his life.

“His exact words were, ‘I’ve done some really interesting things in my life, but I just wish it hadn’t hurt so many people,’ ” Wilcox recalled. DePugh, he said, was referring to his estranged family. “His life was pretty tragic,” Wilcox said.

DePugh died June 30 at age 86 at his home. Per his request, no funeral was held, and donations were solicited to pay for his cremation.

The death of the man who had appeared on the front page of the New York Times and whose shadow army made elected officials quake in fear warranted almost no media coverage. A scant two-line obituary ran in the Kansas City Star. The obit misspelled his middle name.

In the 1960s if you entered a restroom or a phone booth, there’s a chance you might have noticed a three-inch-square sticker at eye level. A closer look might show the image of a rifle crosshairs superimposed over a menacing text:

“See that old man at the corner where you buy your papers?” the sticker read. “He may have a silencer equipped pistol under his coat. That fountain pen in the pocket of the insurance salesman that calls on you might be a cyanide gas gun. What about your milkman? Arsenic works slow but sure. … Traitors, beware! Even now the crosshairs are on the back of your necks.”

The author of this screed is Robert Bolivar DePugh, and his goal was terror. For more than a decade, DePugh led a shadowy militia group known as the Minutemen. Their stated purpose was to use guerilla warfare to repel the Communist invasion they always believed was at hand. Later, they vowed to root out Communist spies they swore were entrenched in the U.S. government. War, in their minds, was always imminent, and a group of armed patriots was the last best hope for the Republic.

“He saw himself as the Paul Revere of the 20th century, that he was going to save the United States from Communism,” said Eric Beckemeier, who grew up in DePugh’s adopted hometown of Norborne and wrote a book in 2007 chronicling his movement. “It was delusions of grandeur, almost.”

DePugh was named after the revolutionary South American fighter Simon Bolivar and was raised in Independence by a father who was a Jackson County sheriff’s deputy. He bounced around several colleges in the 1940s, including a stint at the University of Missouri. In 1943, he enlisted in the Army but was discharged the next year after a psychological review noted psychoneurosis.

By the late 1950s, though, DePugh was a relative success. He had made a small fortune in veterinary medicine when he founded Biolab Corp. and created a vitamin that promised to lengthen the lifespan of dogs. The tiny town of Norborne, which is about 100 miles northwest of Columbia, actively recruited DePugh to move his company there, believing he would bring jobs.

Instead he brought ignominy.

DePugh used Norborne as a home base from which to recruit dissidents from all over the nation. He printed and mailed out a monthly magazine, “On Target,” and authored several popular books. His themes of self-reliance, ultra-patriotism and paranoid anti-communism struck a chord with people on the fringes.

“Within that little narrow range of people, he was sort of charismatic,” said Harry Jones, a longtime Kansas City Star reporter who covered DePugh and wrote a book about the Minutemen in 1968. “But his ideas were so out of whack with what most people were thinking that the great majority of people laughed him off as a kook.”

But it was impossible to laugh at the cache of arms and explosives DePugh was building up or dismiss his paramilitary training sessions, where men crawled on their bellies and practiced marksmanship and booby-trapping. Loosely affiliated groups began to sprout up in other states under the same Minutemen banner, and DePugh bragged that his network was tens of thousands large. Newspapers repeated his claims.

“Various liberal interest groups and newspapers were giving figures of 50,000 or 100,000 people, and it just wasn’t true,” said Laird Wilcox, an expert on extremists and founder of the Wilcox Collection of Contemporary Political Movements at the University of Kansas. “There were just a few hundred people who were active in that thing. … There wasn’t much of an underground to it at all.”

But DePugh had a knack for the spotlight. He named names of Communists — including Lucille Ball and Humphrey Bogart, among others — and he published a list of 20 congressmen he wanted dead. Attorney General Robert Kennedy ordered his movements closely watched, and FBI agents infiltrated his group.

In 1967, thanks to this federal scrutiny and the vast stores of illegal weapons he stashed around the area, DePugh was convicted of violating the National Firearms Act. Before serving his sentence, he and another Minutemen fled to New Mexico and lived on the lam for two years.

From there on, his life more or less unraveled. In 1969, DePugh was caught in Truth or Consequences, N.M., after a massive manhunt. According to multiple reports, agents found him holding two former Minutemen — a man and a woman — in confinement crates because he believed they were traitors. He also had large stores of weapons. DePugh spent four years in federal prison and wrote a book about the plight of the incarcerated. Many consider it his best and most compassionate work.

During the late ’60s, authorities tried to connect him to various other Minutemen exploits, including a bank robbery in Seattle and a planned cyanide attack on the United Nations, but they were unsuccessful. DePugh credibly said that he had no control over the people who were nominally his followers.

In 1991, police in Iowa arrested him on charges of child pornography after a modeling shoot he took of a teenage girl. DePugh beat those charges as well, but some close to him considered it the last straw and severed their ties to him.

In more recent years, DePugh lived alone in an apartment beneath a storefront church in Richmond, Mo.

Beckemeier, who received a mailing from the prolific polemicist, said DePugh’s political views continued to be bizarre and often contradictory late into his life.

“His writings were anti-Bush, pro-Obama and anti-Semitic, all at the same time,” Beckemeier said. “That’s quite a combination.”

But his life was lonely. His wife had divorced him, and his children mostly had stopped speaking to him. He suffered from ALS disease. Wilcox, who lives in Olathe, Kan., last visited DePugh five years ago and said the man had deep regrets about his life.

“His exact words were, ‘I’ve done some really interesting things in my life, but I just wish it hadn’t hurt so many people,’ ” Wilcox recalled. DePugh, he said, was referring to his estranged family. “His life was pretty tragic,” Wilcox said.

DePugh died June 30 at age 86 at his home. Per his request, no funeral was held, and donations were solicited to pay for his cremation.

The death of the man who had appeared on the front page of the New York Times and whose shadow army made elected officials quake in fear warranted almost no media coverage. A scant two-line obituary ran in the Kansas City Star. The obit misspelled his middle name.

JohnFester- Posts : 824

Join date : 2015-06-01

Age : 67

Location : Hollyweird, Calif.

JohnFester- Posts : 824

Join date : 2015-06-01

Age : 67

Location : Hollyweird, Calif.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

FBI arrests right-wing Minutemen on January 26, 1968, for conspiring to blow up Redmond City Hall and rob four banks.

HistoryLink.org Essay 1464 : Printer-Friendly Format

On January 26, 1968, the FBI arrests seven members of the Minutemen, a right-wing paramilitary organization, for conspiracy in their plans to blow up the Redmond City Hall and power stations, and to rob four banks. Agents seize 10 Molotov cocktail firebombs, nine sticks of dynamite, blasting caps, face masks, and three pistols. A total of nine men, including national Minutemen leader Robert Bolivar DePugh, will be convicted in the scheme, which they claim is "an organizational rehearsal" ("7 Are Convicted ...") for the time when, in their view, Communists would take control of the United States.

DePugh's View

Veterinary pharmaceutical manufacturer and businessman Robert Bolivar DePugh of Norborne, Missouri, organized the Minutemen in 1960 in response to his fear that Communists would take over the United States. He named and patterned the group after the colonial American militia. A year later he claimed a membership of 25,000, employed as members of "combat teams," "intelligence or espionage work," and in "communications, weapons, or medical" ("Minutemen, Upset ..."). News reports set national membership at a few thousand.

DePugh published a monthly magazine, On Target. In 1966, he organized the Minutemen as the Patriotic Party to run local and Congressional candidates in the 1968 election. Later in 1966 and in 1967, he was convicted of federal firearms violations and conspiracy, but was released on bond pending an appeal.

Plans to Bomb

With the assistance of Henry Edward Warren, the FBI kept the group under visual and electronic surveillance until January 26, 1968, when the conspirators were arrested in Lake City and in Bellevue as they were preparing their assault. Seized at the time were guns, dynamite, masks, gasoline bombs, rubber gloves, maps with escape routes marked, floor plans of targeted banks in Redmond, and even brass knuckles.

The group had planned to disable police response by bombing the Redmond Police Department and a power station in Redmond. Tipped off by the FBI as to the exact date of the attack, city officials quietly evacuated City Hall except for a skeleton staff in the police offices.

A Federal grand jury at Seattle charged the following men with conspiracy:

•Kelley E. Delano, 24

•Duane I. Carlson, 35

•Milton J. Dix, 34

•Jerome Riemart, 43

•Mervin Henderson Sr., 57

•Joseph Hourie, 20

•Ervin J. White, 41

The grand jury also charged DePugh and his "executive assistant" ("Minuteman Chief ..."), Walter Patrick Payson, with conspiracy in the same case, but both DePugh and Payson went into hiding. The original seven went to trial in Spokane because excessive publicity in the Seattle area tainted the jury pool there.

Warren testified against the defendants and described the plot to net between $87,000 and $100,000. Each participant would receive $1,000 plus $100 a month while in hiding. "However it was later decided that we would use Molotov cocktails to start two diversionary fires. We also planned to acquire either chloroform or ether to put everyone in the police station and banks to sleep" ("7 Are Convicted ..."). Ervin White testified that what Warren said was true, but "That the entire scheme was merely an organization rehearsal" ("7 Are Convicted ..."). On June 22, 1968, the jury found all seven defendants guilty.

DePugh and Payson remained at large until they were arrested near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, on July 13, 1969. DePugh was sentenced to a total of more than 11 years in prison and was paroled less than four years later.

HistoryLink.org Essay 1464 : Printer-Friendly Format

On January 26, 1968, the FBI arrests seven members of the Minutemen, a right-wing paramilitary organization, for conspiracy in their plans to blow up the Redmond City Hall and power stations, and to rob four banks. Agents seize 10 Molotov cocktail firebombs, nine sticks of dynamite, blasting caps, face masks, and three pistols. A total of nine men, including national Minutemen leader Robert Bolivar DePugh, will be convicted in the scheme, which they claim is "an organizational rehearsal" ("7 Are Convicted ...") for the time when, in their view, Communists would take control of the United States.

DePugh's View

Veterinary pharmaceutical manufacturer and businessman Robert Bolivar DePugh of Norborne, Missouri, organized the Minutemen in 1960 in response to his fear that Communists would take over the United States. He named and patterned the group after the colonial American militia. A year later he claimed a membership of 25,000, employed as members of "combat teams," "intelligence or espionage work," and in "communications, weapons, or medical" ("Minutemen, Upset ..."). News reports set national membership at a few thousand.

DePugh published a monthly magazine, On Target. In 1966, he organized the Minutemen as the Patriotic Party to run local and Congressional candidates in the 1968 election. Later in 1966 and in 1967, he was convicted of federal firearms violations and conspiracy, but was released on bond pending an appeal.

Plans to Bomb

With the assistance of Henry Edward Warren, the FBI kept the group under visual and electronic surveillance until January 26, 1968, when the conspirators were arrested in Lake City and in Bellevue as they were preparing their assault. Seized at the time were guns, dynamite, masks, gasoline bombs, rubber gloves, maps with escape routes marked, floor plans of targeted banks in Redmond, and even brass knuckles.

The group had planned to disable police response by bombing the Redmond Police Department and a power station in Redmond. Tipped off by the FBI as to the exact date of the attack, city officials quietly evacuated City Hall except for a skeleton staff in the police offices.

A Federal grand jury at Seattle charged the following men with conspiracy:

•Kelley E. Delano, 24

•Duane I. Carlson, 35

•Milton J. Dix, 34

•Jerome Riemart, 43

•Mervin Henderson Sr., 57

•Joseph Hourie, 20

•Ervin J. White, 41

The grand jury also charged DePugh and his "executive assistant" ("Minuteman Chief ..."), Walter Patrick Payson, with conspiracy in the same case, but both DePugh and Payson went into hiding. The original seven went to trial in Spokane because excessive publicity in the Seattle area tainted the jury pool there.

Warren testified against the defendants and described the plot to net between $87,000 and $100,000. Each participant would receive $1,000 plus $100 a month while in hiding. "However it was later decided that we would use Molotov cocktails to start two diversionary fires. We also planned to acquire either chloroform or ether to put everyone in the police station and banks to sleep" ("7 Are Convicted ..."). Ervin White testified that what Warren said was true, but "That the entire scheme was merely an organization rehearsal" ("7 Are Convicted ..."). On June 22, 1968, the jury found all seven defendants guilty.

DePugh and Payson remained at large until they were arrested near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, on July 13, 1969. DePugh was sentenced to a total of more than 11 years in prison and was paroled less than four years later.

JohnFester- Posts : 824

Join date : 2015-06-01

Age : 67

Location : Hollyweird, Calif.

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

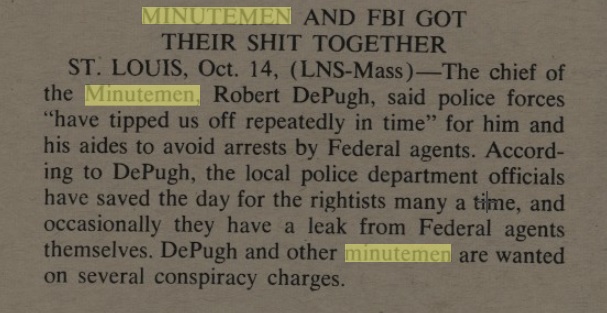

oct 18, 1968

Sick E. Von Brutal- Posts : 720

Join date : 2016-04-09

Age : 41

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

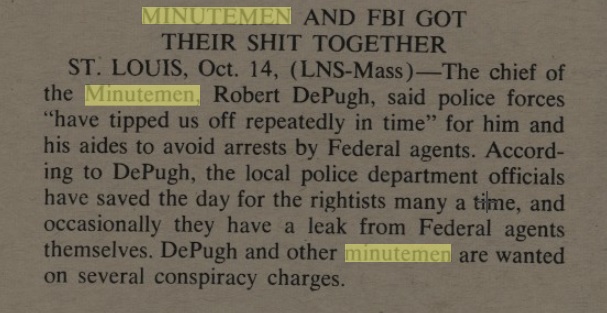

may 6 1966 Berkeley barb

Sick E. Von Brutal- Posts : 720

Join date : 2016-04-09

Age : 41

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

Re: Minutemen newspaper articles

nov. 1966 Berkeley barb

Sick E. Von Brutal- Posts : 720

Join date : 2016-04-09

Age : 41

Similar topics

Similar topics» Newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

» Ted. K newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

» Ted. K newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

» Newspaper articles

NOW LOCATED AT https://theslaughterhouse.freeforums.net/ :: WE HAVE RELOCATED TO https://theslaughterhouse.freeforums.net/ :: Troy Houghton and the Minutemen

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum